Today, social media, artificial intelligence, and algorithms are taking over our lives in ways that were unconceivable even for the most visionary sci-fi author. We are witnessing an historical turning point in which the way we perceived, practiced or performed a lot of activities is drastically changing. How we do art, what kinds of jobs there are left for humans, how much our relationships with machines will impact on all the others, and the list could be endless. We are attempting to make sense of it with the little tools we have so far, and as my educational mindset of archaeologist imposes, I tend to go back to the past, not for answers neither for comfort, that would be silly, mostly it is to look for a perspective, to escape the present so as not to be overwhelmed by it and not being enslaved by the tyranny of the headlines.

Of all the museums I have visited in Brussels, the story of La Fonderie is paradigmatic for the days we are living because it is one of those cases in which the idea of a museum stems directly from the urgency of the citizens to preserve the tangible and intangible traces and the memory of the area, the history of the industries that once flourished along the canal, its workers, its inhabitants and their stories.

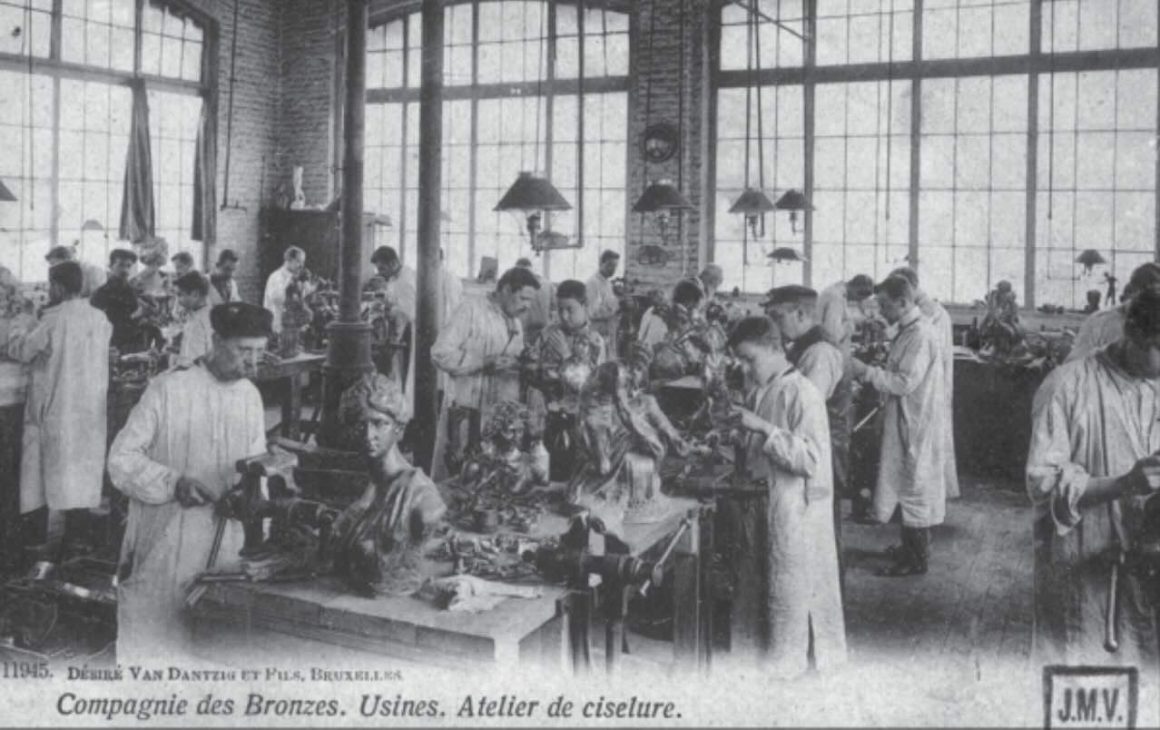

But how did we get to the museum? To understand this, we need to briefly go back to the rise and fall of La Compagnie des Bronzes, which was one of the most renowned factories for bronzes and especially monumental ones. Imagine a relentless parade, in the small rue Ransfort, of lions and animals of the most disparate species, muscular bodies in the boldest, most artistic poses, national heroes, representants of ancient guilds, and many more, all coming out from the most important bronze atelier in the city. If you want to materialize the previous list just wander around Brussels, at the Congress Column you will find the lions, at the Grand Place the statue of ‘t Serclaes, at Petit Sablon the 48 statues of the ancient professions, but also on the façade of the Royal Museums, at the Botanical Garden, at the entrance of the Bois de la Cambre and the list could continue… a frenzy in the creation of images for which the term statuomanie was coined, for which the Compagnie played a central role.

Started as a family business, the future Compagnie des Bronzes was founded in 1854 nearby the cathedral, for the “confection and sale of items made of zinc, copper iron and other metals”; soon the production was extended to decorative objects and furniture and most importantly, to the monumental bronzes coming from public commissions which made it necessary to move the production to the Molenbeek location. Public commissions which objective was to celebrate the heritage of the newly independent regions, to enlighten citizens, pedestrians, and the broader public regarding the legendary or actual contributions of historical and modern personalities, and to adorn public spaces. Among the most distinguished Belgian sculptors of the century participated in illustrating the city such as public: Paul De Vigne, Julien Dillens, Guillaume Geefs, Jef Lambeaux, Eugène Simonis, Thomas Vinçotte, among them an emerging Auguste Rodin.

Did you know? The fences of the New York zoo in the Bronx were made by La Compagnie des Bronzes!

La Compagnie contributed not only to the embellishment of the city but also to the social development of the working class, it is important to observe the participation of numerous company employees in the formation of a structured labor movement, which subsequently gave rise to the Belgian Workers’ Party, not only in the capital but also nationwide.

After WWII and the completion of the city’s last major construction projects (Royal Library, National Bank) the Compagnie fails to adapt and evolve, seen that bronze is not fashionable anymore as material to decorate the house and public commissions collapse, the last bronze casting is performed on the 30th of April 1977. The Compagnie sells the site and the factory and move to a smaller place in Anderlecht culminating in the abandonment and destruction of hundreds of plaster models. In 1979 the company declares bankruptcy. Here is where the story of the future museum begins, in 1981 the Collectif Fonderie du Vieux Molenbeek manages to save the site convincing the French community to acquire it. The collective is committed to preserving the memory of industrial and working-class neighborhoods and, through local engagement, to rehabilitating them and defending the most vulnerable residents. These objectives are achieved through the restoration of buildings and public spaces, the creation of community facilities, the fight against real estate speculation, and the return of the city to its inhabitants. In 1983 the collective becomes an ASBL (non-profit association) and rescued the tools, furniture, plaster casts, drawings, and archives that had been left derelict on the site, establishing there in 1986. This extensive array of documents and materials brought up the idea of a museum that could tell not only the story of La Compagnie des Bronzes but also the industrial, social and labor history for the Brussels region. It has a documentation center and a photo library, collecting testimonies of oral memory and in 2001 the turners’ hall is reconverted into what is known today as the Brussels Museum of Industry and Labour. The museum hosts a very diverse collection of objects, archives, tools and machines (only a small part is displayed though), coming from different factories which were preserved amidst deindustrialization, frequently under urgent circumstances. As always in this column I have picked a few examples from the collection, and I leave the discovery to you.

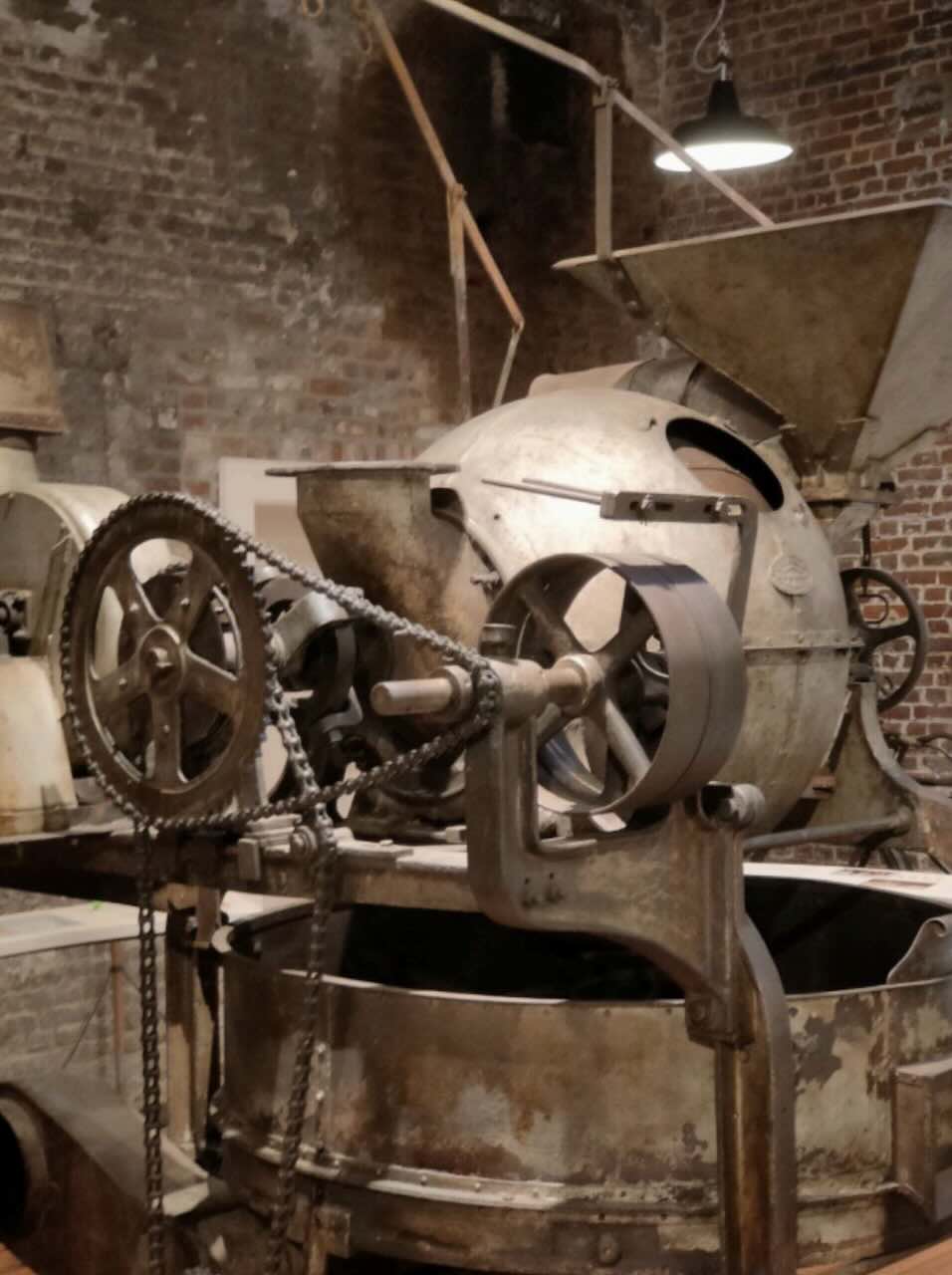

The Sirocco Roaster

Chocolate has become one of the most popular symbols of the Belgian food culture and this association dates to the Spanish domination. Nevertheless, one specific detail tends to be disregarded: cocoa beans began to be imported from the Belgian Congo in the 20th century. The roaster can be a means to raise deeper questions about what, how and why we consume something. A nice thing that you find among the description of the machine is a small paragraph about Ak Yaçar, a chocolate worker, who worked on this machine until 1988 and remembered its functionality.

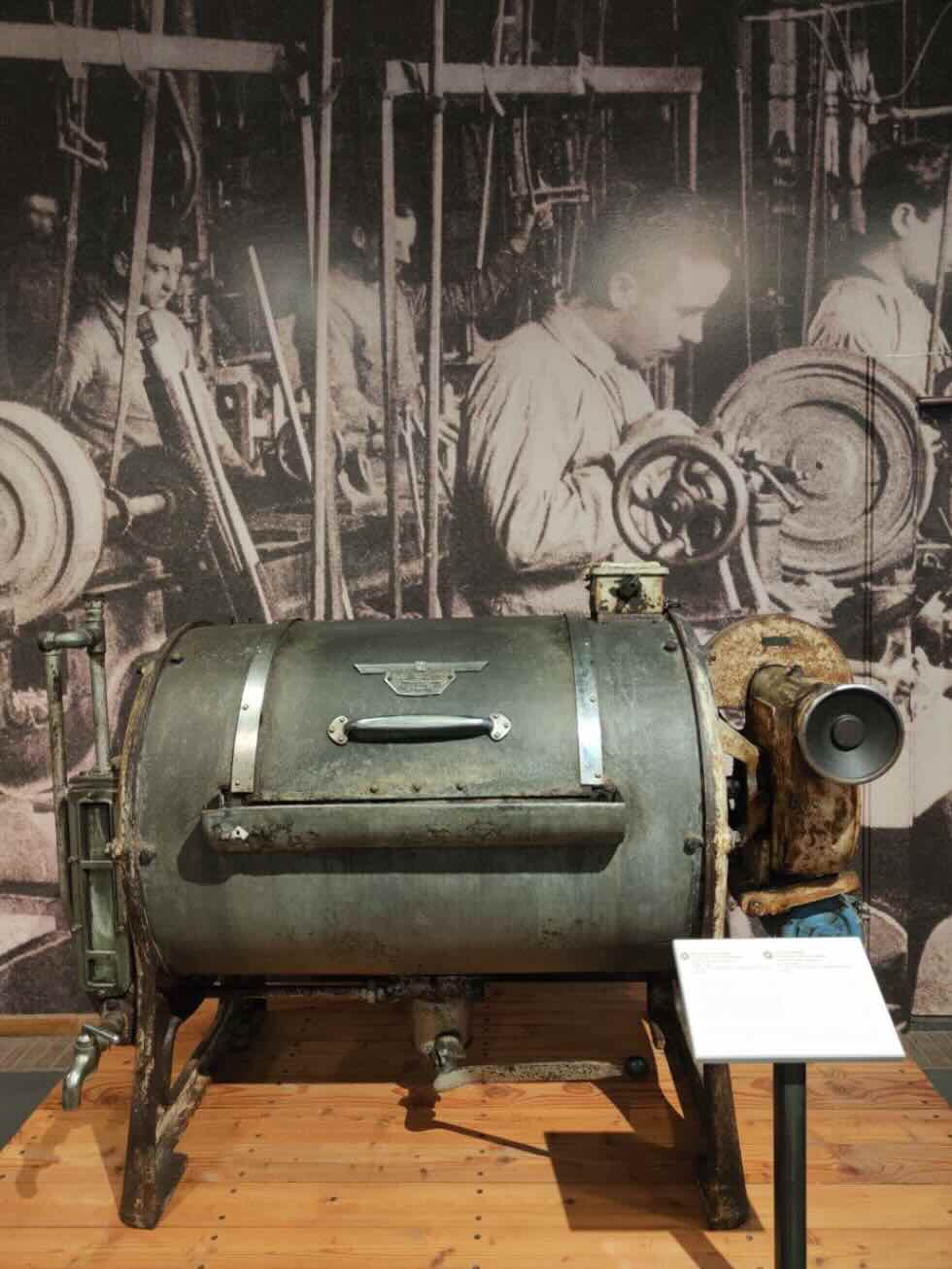

The Washing Machine

We can see these machines as spacetime windows allowing us to project ourselves to a past that seems far, a past in which the emancipation of women passed by technological innovations as well. Laundry was a rather tiring chore that burdened women. Looking at this machine from the 1950’s prompts us to consider what has been achieved and what still lies ahead.

Linotype

I would first say that I was very impressed by the beauty of the machine itself before learning what its function was. The Linotype was a revolutionary instrument for publishing, speeding up the typographic work significantly boosting production. This machine also functions as an intermediary into past, present and future. It allows us to think and rethink our relationship with books, for instance, how they shape our lives and what their future will be as the “digital threat” is always there, looming on their very existence.

The museum also hosts temporary exhibitions, which is something they have done even before the museum existed (the first exhibition organized by La Fonderie was held in Tour & Taxis in 1986 under the title Bruxelles, un canal, des usines et des hommes). They have recently opened a brand new one which is quite peculiar and perfectly aligned with contemporary issues, not only in Belgium but worldwide, called BELDAVIA – Votre nouvelle terre d’acceuil (your new host country). It is an interactive exhibition that fully engages the public in questioning received ideas on migration policies, access to housing, social integration and cohesion, discrimination, and access to fundamental rights by experiencing firsthand the arduous ordeal a person faces when, for differing motives, they are forced to abandon their native land and depend on the welcome of a foreign country. Upon your arrival in Beldavia, you spin the wheel of misfortune, which assigns you a path and an identity. Your trajectory will vary depending on your choices and the reason for your departure.

La Fonderie, rue Ransfort 27, Brussels

Opening hours: Open Tuesday through Sunday, from 10:00 to 17:00 (final admission at 15:30).

Beldavia exhibition until 28.06.2026